[/caption]

[/caption]DESCRIPTION

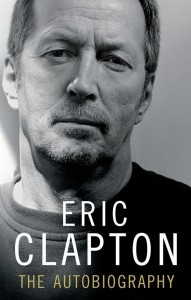

“I found a pattern in my behavior that had been repeating itself for years, decades even. Bad choices were my specialty, and if something honest and decent came along, I would shun it or run the other way.”With striking intimacy and candor, Eric Clapton tells the story of his eventful and inspiring life in this poignant and honest autobiography. More than a rock star, he is an icon, a living embodiment of the history of rock music. Well known for his reserve in a profession marked by self-promotion, flamboyance, and spin, he now chronicles, for the first time, his remarkable personal and professional journeys. Born illegitimate in 1945 and raised by his grandparents, Eric never knew his father and, until the age of nine, believed his actual mother to be his sister. In his early teens his solace was the guitar, and his incredible talent would make him a cult hero in the clubs of Britain and inspire devoted fans to scrawl “Clapton is God” on the walls of London’s Underground. With the formation of Cream, the world's first supergroup, he became a worldwide superstar, but conflicting personalities tore the band apart within two years. His stints in Blind Faith, in Delaney and Bonnie and Friends, and in Derek and the Dominos were also short-lived but yielded some of the most enduring songs in history, including the classic “Layla.” During the late sixties he played as a guest with Jimi Hendrix and Bob Dylan, as well as the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and longtime friend George Harrison. It was while working with the latter that he fell for George’s wife, Pattie Boyd, a seemingly unrequited love that led him to the depths of despair, self-imposed seclusion, and drug addiction. By the early seventies he had overcome his addiction and released the bestselling album 461 Ocean Boulevard, with its massive hit “I Shot the Sheriff.” He followed that with the platinum album Slowhand, which included “Wonderful Tonight,” the touching love song to Pattie, whom he finally married at the end of 1979. A short time later, however, Eric had replaced heroin with alcohol as his preferred vice, following a pattern of behavior that not only was detrimental to his music but contributed to the eventual breakup of his marriage. In the eighties he would battle and begin his recovery from alcoholism and become a father. But just as his life was coming together, he was struck by a terrible blow: His beloved four-year-old son, Conor, died in a freak accident. At an earlier time Eric might have coped with this tragedy by fleeing into a world of addiction. But now a much stronger man, he took refuge in music, responding with the achingly beautiful “Tears in Heaven.”Clapton is the powerfully written story of a survivor, a man who has achieved the pinnacle of success despite extraordinary demons. It is one of the most compelling memoirs of our time.PREVIEW

[lyrics]To my grandmother, Rose Amelia Clapp,

to my beloved wife, Melia,

and to my children, Ruth, Julie, Ella, and Sophie

Early in my childhood, when I was about six or seven, I began to get the feeling that there was something different about me. Maybe it was the way people talked about me as if I weren’t in the room. My family lived at 1, the Green, a tiny house in Ripley, Surrey, which opened directly onto the village Green. It was part of what had once been almshouses and was divided into four rooms; two poky bedrooms upstairs, and a small front room and kitchen downstairs. The toilet was outside, in a corrugated iron shed at the bottom of the garden, and we had no bathtub, just a big zinc basin that hung on the back door. I don’t remember ever using it.

Twice a week my mum used to fill a smaller tin tub with water and sponge me down, and on Sunday afternoons I used to go and have a bath at my Auntie Audrey’s, my dad’s sister, who lived in the new flats on the main road. I lived with Mum and Dad, who slept in the main bedroom overlooking the Green, and my brother, Adrian, who had a room at the back. I slept on a camp bed, sometimes with my parents, sometimes downstairs, depending on who was staying at the time. The house had no electricity, and the gas lamps made a constant hissing sound. It amazes me now to think that whole families lived in these little houses.

My mum had six sisters: Nell, Elsie, Renie, Flossie, Cath, and Phyllis, and two brothers, Joe and Jack. On a Sunday it wasn’t unusual for two or three of these families to show up, and they would pass the gossip and get up-to-date with what was happening with us and with them. In the smallness of this house, conversations were always being carried on in front of me as if I didn’t exist, with whispers exchanged between the sisters. It was a house full of secrets. But bit by bit, by carefully listening to these exchanges, I slowly began to put together a picture of what was going on and to understand that the secrets were usually to do with me. One day I heard one of my aunties ask, “Have you heard from his mum?” and the truth dawned on me, that when Uncle Adrian jokingly called me a little bastard, he was telling the truth.

The full impact of this realization upon me was traumatic, because at the time I was born, in March 1945—in spite of the fact that it had become so common because of the large number of overseas soldiers and airmen passing through England—an enormous stigma was still attached to illegitimacy. Though this was true across the class divide, it was particularly so among working-class families such as ours, who, living in a small village community, knew little of the luxury of privacy. Because of this, I became intensely confused about my position, and alongside my deep feelings of love for my family there existed a suspicion that in a tiny place like Ripley, I might be an embarrassment to them that they always had to explain.

The truth I eventually discovered was that Mum and Dad, Rose and Jack Clapp, were in fact my grandparents, Adrian was my uncle, and Rose’s daughter, Patricia, from an earlier marriage, was my real mother and had given me the name Clapton. In the mid-1920s, Rose Mitchell, as she was then, had met and fallen in love with Reginald Cecil Clapton, known as Rex, the dashing and handsome, Oxford-educated son of an Indian army officer. They had married in February 1927, much against the wishes of his parents, who considered that Rex was marrying beneath him. The wedding took place a few weeks after Rose had given birth to their first child, my uncle Adrian. They set up home in Woking, but sadly, it was a short-lived marriage, as Rex died of consumption in 1932, three years after the birth of their second child, Patricia.

Rose was heartbroken. She returned to Ripley, and it was ten years before she was married again, after a long courtship on his part, to Jack Clapp, a master plasterer. They were married in 1942, and Jack, who as a child had badly injured his leg and therefore been exempt from call-up, found himself stepfather to Adrian and Patricia. In 1944, like many other towns in the south of England, Ripley found itself inundated with troops from the United States and Canada, and at some point Pat, age fifteen, enjoyed a brief affair with Edward Fryer, a Canadian airman stationed nearby. They had met at a dance where he was playing the piano in the band. He turned out to be married, so when she found out she was pregnant, she had to cope on her own. Rose and Jack protected her, and I was born secretly in the upstairs back bedroom of their house on March 30, 1945. As soon as it was practical, when I was in my second year, Pat left Ripley, and my grandparents brought me up as their own child. I was named Eric, but Ric was what they all called me.

Rose was petite with dark hair and sharp, delicate features, with a characteristic pointed nose, “the Mitchell nose,” as it was known in the family and which was inherited from her father, Jack Mitchell. Photographs of her as a young woman show her to have been very pretty, quite the beauty among her sisters. But at some point at the outset of the war, when she had just turned thirty, she underwent surgery for a serious problem with her palate. During the operation there was a power cut that resulted in the surgery having to be abandoned, leaving her with a massive scar underneath her left cheekbone that gave the impression that a piece of her cheek had been hollowed out. This left her with a certain amount of self-consciousness. In his song “Not Dark Yet,” Dylan wrote, “Behind every beautiful face there’s been some kind of pain.” Her suffering made her a very warm person with a deep compassion for other people’s dilemmas. She was the focus of my life for much of my upbringing.

Jack, her second husband and the love of her life, was four years younger than Rose. A shy, handsome man, over six feet tall with strong features and very well built, he had a look of Lee Marvin about him and used to smoke his own roll-ups, made from a strong, dark tobacco called Black Beauty. He was authoritarian, as fathers were in those days, but he was kind, and very affectionate to me in his way, especially in my infant years. We didn’t have a very tactile relationship, as all the men in our family found it hard to express feelings of affection or warmth. Perhaps it was considered a sign of weakness. Jack made his living as a master plasterer, working for a local building contractor. He was a master carpenter and a master bricklayer, too, so he could actually build an entire house on his own.

An extremely conscientious man with a very strong work ethic, he brought in a very steady wage, which didn’t ever fluctuate for the whole time I was growing up, so although we could have been considered poor, we rarely had a shortage of money. When things occasionally did get tight, Rose would go out and clean other people’s houses, or work part-time at Stansfield’s, a bottling company with a factory on the outskirts of the village that produced fizzy drinks such as lemonade, orangeade, and cream soda. When I was older I used to do holiday jobs there, sticking on labels and helping with deliveries, to earn pocket money. The factory was like something out of Dickens, reminiscent of a workhouse, with rats running around and a fierce bull terrier that they kept locked up so it wouldn’t attack visitors.

Ripley, which is more like a suburb today, was deep in the country when I was born. It was a typical small rural community, with most of the residents being agricultural workers, and if you weren’t careful about what you said, then everybody knew your business. So it was important to be polite. Guildford was the main shopping town, which you could get to by bus, but Ripley had its own shops, too. There were two butchers, Conisbee’s and Russ’s, and two bakeries, Weller’s and Collins’s, a grocer’s, Jack Richardson’s, Green’s the paper shop, Noakes the ironmonger, a fish-and-chip shop, and five pubs. King and Olliers was the haberdashers where I got my first pair of long trousers, and it doubled as a post office, and we had a blacksmith where all the local farm horses came in for shoes.

Every village had a sweet shop; ours was run by two old-fashioned sisters, the Miss Farrs. We would go in there and the bell would go ding-a-ling-a-ling, and one of them would take so long to come out from the back of the shop that we could fill our pockets up before a movement of the curtain told us she was about to appear. I would buy two Sherbert Dabs or a few Flying Saucers, using the family ration book, and walk out with a pocketful of Horlicks or Ovaltine tablets, which had become my first addiction.

In spite of the fact that Ripley was, all in all, a happy place to grow up in, life was soured by what I had found out about my origins. The result was that I began to withdraw into myself. There seemed to have been some definite choices made within my family regarding how to deal with my circumstances, and I was not made privy to any of them. I observed the code of secrecy that existed in the house—“We don’t talk about what went on”—and there was also a strong disciplinarian authority in the household, which made me nervous about asking any questions. On reflection, it occurs to me that the family had no real idea of how to explain my own existence to me, and that the guilt attached to that made them very aware of their own shortcomings, which would go a long way in explaining the anger and awkwardness that my presence aroused in almost everybody. As a result I attached myself to the family dog, a black Labrador called Prince, and created a character for myself, whose name was “Johnny Malingo.” Johnny was a suave, devil-may-care man/boy of the world who rode roughshod over anyone who got in his way. I would escape into Johnny when things got too much for me, and stay there until the storm had passed. I also invented a fantasy friend called Bushbranch, a small horse who went with me everywhere. Sometimes Johnny would magically become a cowboy and climb onto Bushbranch, and together they would ride off into the sunset. At the same time, I started to draw quite obsessively. My first fascination was with pies. A man used to come to the village Green pushing a barrow, which was his container for hot pies. I had always loved pies—Rose was an excellent cook—and I produced hundreds of drawings of them and of the pie man. Then I turned to copying from comics.

Because I was illegitimate, Rose and Jack tended to spoil me. Jack actually made my toys for me. I remember, for example, a beautiful sword and shield that he made me by hand. It was the envy of all the other kids. Rose bought me all the comics I wanted. I seemed to get a different one every day, always The Topper, The Dandy, The Eagle, and The Beano. I particularly loved the Bash Street Kids, and I always used to notice when the artists would change and Lord Snooty’s top hat would be different in some way. Over the years I copied countless drawings from these comics—cowboys and Indians, Romans, gladiators, and knights in armor. Sometimes at school I did no classwork at all, and it became quite normal to see all of my textbooks full of nothing but drawings.

School for me began when I was five, at Ripley Church of England Primary School, which was situated in a flint building next to the village church. Opposite was the village hall, where I attended Sunday school, and where I first heard a lot of the old, beautiful English hymns, my favorite of which was “Jesus Bids Us Shine.” At first I was quite happy going to school. Most of the kids who lived on the Green next to us started at the same time, but as the months went by, and it dawned on me that this was it for the long haul, I began to panic. The feelings of insecurity I had about my home life made me hate school. All I wanted to be was anonymous, which kept me out of entering any kind of competitive event. I hated anything that would single me out and get me unwanted attention.

I also felt that sending me to school was just a way of getting me out of the house, and I became very resentful. One master, quite young, a Mr. Porter, seemed to have a real interest in unearthing the children’s gifts or skills, and becoming acquainted with us in general. Whenever he tried this with me, I would become extremely resentful. I would stare at him with as much hatred as I could muster, until he eventually caned me for what he called “dumb insolence.” I don’t blame him now; anyone in a position of authority got that kind of treatment from me. Art was the only subject that I really enjoyed, though I did win an award for playing “Greensleeves” on the recorder, which was the first instrument I ever learned to play.

The headmaster, Mr. Dickson, was a Scotsman with a shock of red hair. I had very little to do with him until I was nine years old, when I was called up before him for making a lewd suggestion to one of the girls in my class. While playing on the Green, I had come across a piece of homemade pornography lying in the grass. It was a kind of book, made of pieces of paper crudely stapled together with rather amateurish drawings of genitalia and a typed text full of words I had never heard of. My curiosity was aroused because I hadn’t had any kind of sex education, and I had certainly never seen a woman’s genitalia. In fact, I wasn’t even certain if boys were different from girls until I saw this book.

Once I recovered from the shock of seeing these drawings, I was determined to find out about girls. I was too shy to ask any of the girls I knew at school, but there was this new girl in class, and because she was new, it was open season on her. As luck would have it, she was put at the desk directly in front of me in the classroom, so one morning I plucked up courage and asked her, without any idea of what the words meant, “Do you fancy a shag?” She looked at me with a bemused expression, because she obviously didn’t have a clue what I was talking about, but at playtime she went and told another girl what I’d said, and asked what it meant. After lunch I was summoned to the headmaster’s office, where, after being quizzed as to exactly what I had said to her and being made to promise to apologize, I was bent over and given six of the best. I left in tears, and the whole episode had a dreadful effect on me, as from that point on I tended to associate sex with punishment, shame, and embarrassment, feelings that colored my sexual life for years.

In one respect I was a very lucky child. As much as there was fairly confusing stuff going on at home and dynamics that were difficult to understand, outside there was another whole world of fantasy and the countryside, which I lived in with my pals. Guy, Stuart, and Gordon were my best friends, and we all lived in the same row of houses on the Green. I don’t know if they knew the truth about my origins, and I don’t suppose it would have meant anything if they had. To them I was “El Capitán,” sometimes shortened to “El,” but mostly I was known as “Ric.” Once school was over, we would be outside all the time on our bikes.

My first bike was a James, given to me by Jack after I’d pestered him to give me a Triumph Palm Beach, like the one he had, which was metallic scarlet and cream and was as far as I was concerned the ultimate bike. Because it was a proper grown-up bike, however, and they didn’t make them for kids, he bought me the James instead. Though it was basically the same color scheme, it wasn’t the real thing, and however hard I tried to be grateful, I was really disappointed, and I think I probably showed it. I didn’t let it get me down, though, because by taking one of the brakes off, removing the mudguards, stripping it down, and giving it different tires—the kind for riding over mud—I turned it into what we call a “track” bike.

We’d all meet on the Green after school and decide where we were going to go. In the summer we’d mostly go down to the river Wey, just outside the village. Everybody went there, grown-ups, too, and one particular place was attractive to us because there was a weir. On one side it was seriously deep and we weren’t allowed to swim there—a couple of kids had drowned in that area over the years—but where the weir came down into the shallows and it looked like a kind of waterfall, there were little ledges and pools on either side where it was safe to swim and play around in the mud. Just beyond that it would pan out, deepen up again, and turn into good fishing water, and that’s where I learned to fish.

Rose bought me a rod from a catalog. It was a cheap, very basic bamboo rod, painted green, with a cork handle and a proper fixed reel, but I really loved it from day one. This was the start of my life as a kit junkie. I used to love just to look at it, and I probably played with it as much as I fished with it. We mostly used bread as bait, and because we were fishing near to proper fishermen, we had to be very careful not to get in their way. Normally the best we could hope for was to catch a gudgeon, but one memorable day I caught a fairly big roach that must have weighed a couple of pounds. Another fisherman who was coming up the bank, a real angler, stopped and said, “That’s a pretty decent fish you’ve got there,” and I was over the moon.

When we weren’t down by the river, we would head off to “the Fuzzies.” This was the name for the woods behind the Green, where we used to play serious games of cowboys and Indians, or Germans and English. We created our own version of the Somme in there, digging trenches deep enough for us to stand in and shoot out of. Parts of the woods were so thick with gorse that one could easily get lost, and we called this area “the forbidden city” or “the lost world.” When I was little, I didn’t go into the lost world without an older boy or a gang, because I really did believe that if I went in on my own, I’d never come out. I had my first encounter with a snake in there. I was in the middle of a game and heard a hissing noise. I looked down, standing with my legs slightly apart, and an adder went between them, a big one about three feet long. I went absolutely rigid. I’d never seen a snake before, but Rose was terrified of them and had passed her fear of them on to me. It scared the shit out of me, and I had nightmares about it for ages.

Occasionally, when I was about ten or eleven, we would play games of “kiss-chase” in the Fuzzies, which was the only time girls were involved in our games. The rules were that the girls were given time to hide, and then we went to look for them, and if we found them the prize would be a kiss. Sometimes we played a higher-stakes version of the game in which the discovered girls had to pull down their knickers. But on the whole we were rather frightened of the girls in the village. They seemed aloof and rather powerful, and anyway showed little interest in us, their attentions being reserved for cooler types, like Eric Beesley, who always cut a bit of a dash and was the first one in Ripley with a crew cut. My experience with the pornography had certainly left me with the feeling that any advances made toward a girl would produce some kind of retribution, and I had no intention of getting caned every other day.

On Saturday mornings, quite a lot of us used to go to the pictures in Guildford, to the ABC Minors Club, which was a real treat. We would watch these incredible cliffhanger serials, like Batman, Flash Gordon, and Hopalong Cassidy, and comedians like the Three Stooges and Charlie Chaplin. They always had an emcee and competitions, where we were encouraged to get up onstage and sing or do impersonations, which I dreaded and always avoided. We were no angels, however. When the lights went down, we would all bring out our homemade catapults and fire conkers at the screen.

In the early 1950s, a typical evening’s entertainment for Ripley kids was sitting in the bus shelter watching the traffic, in the vain hope that a sports car would go by, and once every six months we might see an Aston Martin or a Ferrari, which would make our day. We were desperate for excitement, and nothing was quite as exciting as breaking the law…within reason. We might go “scrumping,” stealing apples, on the Dunsborough estate, which in terms of excitement was huge because it was owned by film star Florence Desmond, and we would sometimes see her famous friends walking on the Green. I once got Tyrone Power’s autograph there. Also the likelihood of getting caught was quite high, as gamekeepers were usually prowling around.

Other times we would go shoplifting in Cobham or Woking, mostly stealing silly things like ties or handkerchiefs, or indulge in the occasional bout of vandalizing. For example, we’d get on one of the trains from Guildford that stopped at all the small local stations and choose an empty compartment—the local trains had no corridors—and in between stations we would completely demolish it. We would smash all the mirrors, tear down the maps on the wall, cut up the luggage rack nets with our penknives, slash all the upholstery to ribbons, and then get out at the next station hooting with laughter. The fact that we knew it was wrong, and yet we could do it and get away with it, gave us a huge adrenaline rush. Of course, if we had been caught, it could have meant being sent to Borstal, but miraculously we never were.

Smoking was an important rite of passage in those days, and occasionally we would get our hands on some cigarettes. I remember when I was twelve, getting hold of some Du Mauriers, and I was particularly intrigued by the packaging. With its dark red flip-top box and silver crisscross pattern, it was very sophisticated and grown-up looking. Rose either saw me smoking or found the box in my pocket, and she got me alone and said, “Okay, if you want to smoke, then let’s have a cigarette together. We’ll see if you can really smoke.” She lit up one of these Du Mauriers, and I put it in my mouth and took a puff. “No, no, no!” she said. “Take it down, take it down! That’s not smoking.” I didn’t know what she meant until she said, “You breathe it in, breathe it in.” Then I tried it, and of course I was violently ill and never smoked again till I was twenty-one.

The one thing I didn’t like was fighting, which was a popular pastime among a lot of the kids. Pain and violence frightened me. The two families to avoid in Ripley were the Masterses and the Hills, who were both extremely hard. The Masterses were my cousins, the children of my Auntie Nell, a memorable lady because she suffered from Tourette’s syndrome, though in those days she was just considered a little eccentric. When she spoke, her speech was interspersed with the words “fuck” and “Eddie,” so she would come to the house and say, “Hello, Ric, fuck Eddie. Is your mum in, fuck Eddie?” I absolutely adored her. Her husband, Charlie, was twice her size and covered in tattoos, and they had fourteen sons, the Masters brothers, who were lethal and usually in some kind of trouble. The Hills were also all boys, about ten in all, and they were the village villains, or so it seemed. They were my nemeses. I was always afraid of getting beaten up by them, so whenever they would pick on me, I would tell my cousins, hoping to cause a vendetta between the Hills and the Masterses. Mostly I tried to stay away from all of them.

From the very earliest days, music played a big role in my life because, in the days before TV, it was a very important part of our community experience. On Saturday nights, most of the adults gathered at the British Legion Club to drink and smoke and listen to local entertainers like Sid Perrin, a great pub singer with a powerful voice, who sang in the style of Mario Lanza and whose singing would drift out onto the street, where we would be sitting with a lemonade and a packet of crisps. Another village musician was Buller Collier, who lived in the end house in our row and used to stand outside his front door and play a piano accordion. I loved to watch him, not just for the sound of the squeeze-box, but for its appearance, because it was red and black and it shimmered.

I was more used to hearing the piano, because Rose loved to play. My earliest memories are of her playing a harmonium, or reed organ, she kept in the front room, and later she acquired a small piano. She would also sing, mostly standards, such as “Now Is the Hour,” a popular hit by Gracie Fields, “I Walk Beside You,” and “Bless This House” by Joseph Locke, who was very popular in our house and the first singer to captivate me with the sound of his voice. My own initial attempts at singing took place on the stairs leading up to the bedrooms in our house. I found out that one place had an echo, and I used to sit there singing the songs of the day, mostly popular ballads, and to me it sounded like I was singing on a record.

A good proportion of any musical genes that I may have inherited came from Rose’s family, the Mitchells. Her dad, Granddad Mitchell, a great big man who was a bit of a drinker and a womanizer, played not only the accordion but also the violin, and he used to hang out with a celebrated local busker named Jack Townshend, who played guitar, fiddle, and spoons, and they’d play traditional music together. Granddad lived on Newark Lane, just around the corner from us, and was an important figure in village life, particularly around harvest time, because he owned a traction engine. He was a little strange and not very friendly, and whenever I went round with my Uncle Adrian to see him, he would usually be sitting in his armchair, more often than not quite drunk.

Like Stansfield’s factory, there was something rather Dickensian about the whole thing. We used to visit him a lot, and it was from watching him play the violin that I got the idea to try and play myself. It just seemed so natural and easy for him. My folks got me an old violin from somewhere, and I think I was supposed to learn by just watching and listening, but I was still only ten years old and didn’t have the patience. All I could get out of it was a screeching noise. I just couldn’t grasp the physics of the instrument at all—I had played only the recorder up till then—and I quickly gave it up.

Uncle Adrian, my mother’s brother, who was still living with us when I was small, was an incredible character and a great influence on my life. Because I had been brought up to think of him as my brother, that was the way I always regarded him, even after I found out he was actually my uncle. He was heavily into fashion and fast cars, and owned a succession of Ford Cortinas, which were usually two-tone—peach and cream or something like that—with their interiors upholstered with fur and fake leopard skin and adorned with mascots. When he wasn’t mucking around with his cars, improving their appearance and performance, he was driving them very fast and sometimes crashing them. He was also an atheist who had an obsession with science fiction, and he had a cupboard full of paperbacks by Isaac Asimov and Kurt Vonnegut and other really good stuff.

Adrian was also an inventor, but most of his inventions were concentrated in the domestic sphere, such as his unique “vinegar dispenser.” He had a passion for vinegar, which he would put on everything, even custard. This was frowned on and finally forbidden by Rose. So he designed a secret vinegar dispenser, which basically consisted of a Fairy Liquid bottle, hidden under his armpit, with a tube coming out of it that went down his sleeve. He could then pass his hand over whatever he was eating, and, by secretly squeezing the bottle by lowering his arm, vinegar would invisibly spray over the plate.

He was very musical, too. He played chromatic harmonica, and was a great dancer. He loved to jitterbug and was very good at it. It was an amazing sight to see, because he had extremely long hair, which he kept greased down with tons of Brylcreem. Once he got going, his hair would fall down and cover his face, making him look like a creature from under the sea. He had a record player in his room and used to play me the jazz records he liked, things by Stan Kenton, the Dorsey Brothers, and Benny Goodman. It seemed like outlaw music at the time, and I felt the message coming through.

Most of the music I was introduced to from an early age came from the radio, which was permanently switched on in the house. I feel blessed to have been born in that period because, musically, it was very rich in its diversity. The program that everybody listened to without fail was Two-Way Family Favourites, a live show that linked the British forces serving in Germany with their families at home. It went out at twelve o’clock on Sundays, just when we were sitting down to lunch. Rose always cooked a really good Sunday lunch of roast beef, gravy, and Yorkshire pudding with potatoes, peas, and carrots, followed by something like “spotted dick” pudding and custard, and, with this incredible music playing, it was a real feast for the senses. We would hear the whole spectrum of music—opera, classical, rock ’n’ roll, jazz, and pop—so typically there might be something like Guy Mitchell singing “She Wears Red Feathers,” then a big-band piece by Stan Kenton, a dance tune by Victor Sylvester, maybe a pop song by David Whitfield, an aria from a Puccini opera like La Bohème, and, if I was lucky, Handel’s “Water Music,” which was one of my favorites. I loved any music that was a powerful expression of emotion.

On Saturday mornings I listened to Children’s Favourites introduced by the incredible Uncle Mac. I would be sitting by the radio at nine o’clock waiting for the pips, then the announcement, “Nine o’clock on Saturday morning means Children’s Favourites,” followed by the signature tune, a high-pitched orchestral piece called “Puffing Billy,” and then Uncle Mac himself saying, “Hello, children everywhere, this is Uncle Mac. Good morning to you all.” Then he would play a quite extraordinary selection of music, mixing children’s songs like “Teddy Bear’s Picnic” or “Nellie the Elephant” with novelty songs like “The Runaway Train” and folk songs such as “The Big Rock Candy Mountain,” and occasionally something at the far end of the spectrum, like Chuck Berry singing “Memphis Tennessee,” which hit me like a thunderbolt when I heard it.

One particular Saturday he put on a song by Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee called “Whooping and Hollering.” It had Sonny Terry playing the harmonica, then alternately whooping in falsetto, so fast, and with perfect timing, while Brownie played fast guitar accompaniment. I guess it was the novelty element that made Uncle Mac play it, but it cut through me like a knife, and after that I never missed Children’s Favourites, just in case he played it again, and he did, like on a rotation, over and over.

Music became a healer for me, and I learned to listen with all my being. I found that it could wipe away all the emotions of fear and confusion relating to my family. These became even more acute in 1954, when I was nine and my mother suddenly turned up in my life. By this time she was married, to a Canadian soldier named Frank MacDonald, and she brought with her two young children, my half brother and sister, Brian, who was six, and Cheryl, who was one. We went to meet my mother when she got off the boat at Southampton, and down the gangplank came this very glamorous, charismatic woman, with her auburn hair up high in the fashion of the day. She was very good-looking, though there was a coldness to her looks, a sharpness. She came off the boat laden with expensive gifts that her husband Frank had sent over from Korea, where he had been stationed during the war. We were all given silk jackets with dragons embroidered on them, and lacquered boxes and things like that.

Even though I knew the truth about her by now, and Rose and Jack were aware of this, nobody said anything when we got home, till one evening, when we were all sitting in the front room of our tiny house, and I suddenly blurted out to Pat, “Can I call you Mummy now?” During an awful moment of embarrassment, the tension in the room was intolerable. The unspoken truth was finally out. Then she said in a very kindly way, “I think it’s best, after all they’ve done for you, that you go on calling your grandparents Mum and Dad,” and in that moment I felt total rejection.

Though I tried to accept and understand what she was saying to me, it was beyond my grasp. I had expected that she would sweep me up in her arms and take me away to wherever she had come from. My disappointment was unbearable, and almost immediately turned into hatred and anger. Things quickly became very difficult for everybody. I became surly and withdrawn, rejecting everyone’s affection, as I felt I had been rejected. Only my Auntie Audrey, Jack’s sister, was able to get through, as I was her favorite, and she would come and see me once a week, bringing me toys and sweets, and gently trying to reach me. I would often abuse her and be openly cruel to her, but deep down inside I was very grateful for her love and attention.

Things were not made any easier by the fact that Pat, who was now referred to in public as my “sister,” in order to avoid complicated and embarrassing explanations, stayed on for the better part of a year. Because they’d come from abroad, and the kids had Canadian accents, they were treated like stars in the village and given special treatment. I felt shoved aside. I even resented my little half brother Brian, who looked up to me and always wanted to come out and play with my pals. One day I was having a tantrum and I stormed out of the house onto the Green. Pat came after me, and I just turned on her and shouted, “I wish you’d never come here! I wish you’d go away!”—and in that single moment I remembered just how idyllic my life had really been up until that day. It had been so simple; there was just me and my parents, and even though I knew they were really my grandparents, I was getting all the attention and there was at least love and harmony in the house. With this new complication, it was just impossible to figure out where my emotions were supposed to go.

These events at home had a drastic effect on my school life. In those days, at age eleven, you had to take an exam called the “eleven plus,” which decided where you were going to go next, either to a grammar school for those with the top results, or a secondary modern school for those with lower grades. You took the exam at another school, which meant that we were all piled into buses and driven to a strange place, where we took exam after exam over the course of a whole day. I blanked on everything. I was so frightened by my surroundings and so insecure and scared that I just couldn’t respond, and the result was that I failed miserably. I didn’t particularly care, because going to either Guildford or Woking Grammar School would have meant being separated from my mates, none of whom were academics. They all excelled in physical sports and had a certain amount of scorn for schooling. As for Jack and Rose, if they were at all disappointed, they didn’t really show it.

So I ended up going to St. Bede’s Secondary Modern School in the neighboring village of Send, which is where I really began to make discoveries. It was the summer of 1956, and Elvis was top of the charts. I met a boy at the school who was a newcomer to Ripley. His name was John Constantine. He came from a well-off middle-class family who lived on the outskirts of the village, and we became friends because we were so different from everybody else. Neither of us fit in. While everybody else at school was into cricket and football, we were into clothes and buying 78 rpm records, for which we were scorned and ridiculed. We were known as “the Loonies.” I used to go to his house a lot, and his parents had a radiogram, which was a combination radio and gramophone. It was the first one I had seen. John had a copy of “Hound Dog,” Elvis’s number one, and we played it over and over. There was something about the music that made it totally irresistible to us, plus it was being made by someone not much older than we were, who was like us, but who appeared to be in control of his own destiny, something we could not even imagine.

I got my first record player the following year. It was a Dansette, and the first single I ever bought was “When,” a number one hit for the Kalin Twins that I’d heard on the radio. Then I bought my first album, The “Chirping” Crickets, by Buddy Holly and the Crickets, followed by the soundtrack album of High Society. The Constantines were also the only people I knew in Ripley who had a TV, and we used to watch Sunday Night at the London Palladium, which was the first TV show to have American performers on, who were so far ahead on every level. I had just won a prize at school (for of all things neatness and tidiness), a book on America, so I was particularly obsessed with it. One night they had Buddy Holly on the show, and I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. That was when I saw my first Fender guitar. Jerry Lee Lewis was singing “Great Balls of Fire,” and the bass player had a Fender Precision Bass. It was like seeing an instrument from outer space, and I said to myself: “That’s the future—that’s what I want.” Suddenly I realized I was in a village that was never going to change, yet there on TV was something out of the future. And I wanted to go there.

One teacher at St. Bede’s, Mr. Swan, an art teacher, seemed to recognize that something about me was worthwhile, that I had artistic skills, and he went out of his way to try and help me. He also taught handwriting, and one of the first things he taught me was to write with an Italic pen. I was a little afraid of him, because he was known to be a strong disciplinarian and was very austere, but he was extremely kind to me, which got through to me on some level. So when it came time for me to take the thirteen plus, an exam designed for students who missed passing the eleven plus, I decided that I would try really hard because I owed Mr. Swan something for his kindness. The result was that, with some misgivings, as I knew it would mean leaving all my friends at St. Bede’s, I passed, aged thirteen, into Hollyfield Road School, Surbiton.

Hollyfield meant big changes for me. I was given a bus pass, and every day I had to travel on my own up to Surbiton from Ripley on the Green Line, a half-hour journey, to go to school with people I’d never met. It was very tough the first few days, and hard to know what to do about my old friendships, because I knew that quite a few of them would peter out. At the same time it was very exciting because at last I was out in the big, wide world. Hollyfield was different in that, though it was a regular secondary school, it also contained the junior art department of Kingston Art School. So while we would study normal things like history, English, and math, a couple of days a week we would do nothing but art: figure drawing, still lifes, working with paint and clay. For the first time in my life I actually started shining, and I felt like I was hitting my stride in every way.

As far as my old friends were concerned, I had moved up in the world, and though they knew to a certain extent that this was okay, they still couldn’t help but have a go at me about it. I knew I was on the move. Hollyfield changed my perspective on life. It was a much wilder environment with more exciting people. It was on the edge of London, so we were skipping class a lot, going to pubs, and going into Kingston to buy records at Bentalls, the department store. I was hearing so many new things all at the same time. I became aware of folk music, New Orleans jazz, and rock ’n’ roll all at the same time, and it mesmerized me.

People always say that they remember exactly where they were the day that President Kennedy was assassinated. I don’t, but I do remember walking onto the school playground on the day Buddy Holly died, and the feeling that was there. The place was like a graveyard, and no one could speak, they were in such shock. Of all the music heroes of the time, he was the most accessible, and he was the real thing. He wasn’t a glamour-puss, he had no act as such, he clearly was a real guitar player, and to top it all off, he wore glasses. He was one of us. It was amazing the effect his death had on us. After that, some say the music died. For me it really seemed to burst open.

The art annex at Hollyfield Road School was a short distance away up Surbiton Hill Road, and on the days when we were doing art we would walk up to this building where our teacher put us to work doing still lifes, sculpture, or drawing. On the way up we would pass Bell’s Music Store, a shop that had made its name selling piano accordions when they were all the rage. Then, when the skiffle boom took off, made popular in the mid-fifties by Lonnie Donegan with songs like “Rock Island Line” and “The Grand Coulee Dam,” Bell’s changed track and became a guitar store, and I would always stop and look at the instruments in the window. Since most of the music I liked best was guitar music, I decided that I would like to learn to play, so I badgered Rose and Jack to buy me one. Maybe I harped about it so much they did it to keep me quiet, but, whatever the reason, one day they took the bus up there with me and put a deposit on the instrument I had singled out as being the guitar of my dreams.

The instrument I had set my eyes on was a Hoyer, made in Germany and costing about two pounds. An odd instrument, it looked like a Spanish guitar, but instead of nylon, it had steel strings. It was a curious combination, and for a novice, it was really quite painful to play. Of course, it was a case of putting the cart before the horse, because I couldn’t even tune a guitar let alone play one. I had no one to teach me, so I set about teaching myself, and it was not an easy task.

To begin with, I had not expected the guitar to be quite so big, almost the same size I was. Once I was able to hold it, I couldn’t get my hand round the neck, and I could hardly press the strings down, they were so high. Playing it seemed an impossible task, and I was overwhelmed by the reality of it. At the same time, I was unbelievably excited. The guitar was very shiny and somehow virginal. It was like a piece of equipment from another universe, so glamorous, and as I tried to strum it, I felt like I was really crossing into grown-up territory.

The first song I chose to learn was a folk song, “Scarlet Ribbons,” made popular by Harry Belafonte, but I had also heard a bluesy version by Josh White. I learned it totally by ear, by listening and playing along to the record. I had a small portable tape recorder, my pride and joy, a little reel-to-reel Grundig that Rose had given me for my birthday, and I would record my attempts to play and then listen to them over and over again until I thought I’d got it right. It was made more difficult because, as I later discovered, the guitar was not a very good one. On a more expensive instrument the strings would normally be lower in relation to the fingerboard, to facilitate the movement of the fingers, but on a cheaper or badly made instrument, the strings will be low at the top of the fingerboard, and as they get closer to the bridge they get higher and higher, which makes them hard to press down and painful to play. I got off to a pretty poor start because I almost immediately broke one of the strings, and since I didn’t have any others, I had to learn to play with only five, and played that way for quite a while.

Going to Hollyfield Road School did a lot to enhance my consciousness of image, as I was meeting some heavyweight characters there who had very definite ideas about art and fashion. It had started for me in Ripley with jeans, which in the early days, when I was about twelve, had to be black and have triple green stitching down the outside, very cutting-edge stuff at the time. Italian-style clothes came next, suits with jackets, cut very short, and tapered trousers with winkle-picker shoes. For us, and for most other families in Ripley, everything was bought from catalogs, like the Littlewoods catalog, and, in my case, was altered if necessary by Rose. The guitar went with the beatnik look, which came in the middle of my time at Hollyfield. This consisted of skintight jeans from Moffats, taken in down the inside, a black crew neck pullover, a combat jacket from Millets—complete with “Ban the bomb” signs—and moccasins made up from a kit.

One day I was kneeling in front of the mirror miming to a Gene Vincent record, when one of my mates walked past the open window. He stopped and looked at me, and I’ll never forget the embarrassment I felt, because the truth is that, driven though I was by the music, I was equally driven by the thought of becoming one of those people I had seen on TV, not English pop stars like Cliff Richard, but the Americans such as Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, and Gene Vincent. I knew then that something was calling me, and I wasn’t going to be able to stay in Ripley.

Though I still hadn’t quite got to grips with the actual playing of the guitar, I wanted to look like I knew what I was doing and tried to cultivate the image of what I thought a troubadour should look like. I got a Biro and I wrote on the top surface of the guitar, in huge letters, the words LORD ERIC because I thought that’s what troubadours did. Then I attached a string to the guitar to serve as a strap and imagined myself with a girlfriend, also dressed in beatnik gear, going to play folk music in a coffee bar. The girlfriend materialized in the shape of a very pretty girl, Diane Coleman, who was also attending Hollyfield. She lived in Kingston, and we had a short but intense little fling until sex reared its head, and I panicked. Until then we had become very fond of one another and would spend hours listening to records together in her mum’s front room. My initial career as a troubadour was just as brief. We went out together to a coffee bar about three times, complete with the LORD ERIC guitar, and were both embarrassed, me by being too shy to play and she by witnessing it. Then, just when I thought I’d hit a brick wall, I found another guitar.

There used to be a kind of flea market in Kingston, and I was wandering around one Saturday when I saw a very odd-looking guitar hanging up on one of the stalls. It was acoustic but it had a very narrow-shaped body, almost like a medieval English guitar, and a painting of a naked woman stuck on the back of it. Intuitively I knew it was good. I picked it up and, though I didn’t play it because I didn’t want anyone to hear, it felt perfect, like a dream guitar. I bought it there and then, for two pounds ten (shillings). Don’t ask me where the money came from, possibly cadged from Rose, or “borrowed” from her handbag. I have no real recollection of my financial arrangement back then with my folks. I think I was getting a pretty decent amount of pocket money each week, but it wouldn’t have been beyond me, I’m ashamed to say, to supplement my spending in any way that was open to me.

By now I had mastered some clawhammer, and tried out a few of the folk pieces I had learned on this new guitar. Compared to the Hoyer, I found it very easy to play. The body was quite small and slim, and it had an unconventionally wide and flat fingerboard like a Spanish guitar. The strings were spaced very far apart so you could get your fingers quite easily onto each string without your hand feeling crowded, and it was shallow all the way down, making it delicate and fragile but at the same time easy to play high on the fingerboard as well as low. It turned out to be a George Washburn, a vintage American instrument of great value, originally manufactured by a company in Chicago that had been making guitars since 1864. On the back of the rosewood body someone had stuck on that piece of paper painted with a pinup, and then varnished it over. It was difficult to scrape this off without damaging the wood, and it pissed me off that someone had done this to such a beautiful instrument. At last I had a proper guitar, meant for folk music. Now maybe I could become the troubadour that I thought I was meant to be.

By the time I took my Art A Level, at the age of sixteen, and moved on to Kingston School of Art, on a year’s probation, I was becoming quite proficient as a player and learning new things all the time. I used to frequent a coffee bar in Richmond called L’Auberge. It was on the hill just by the bridge, and across the river in Twickenham was a funky old place called Eel Pie Island. This was an island in the middle of the river, which had a massive dance hall built on it. It was an ancient, creaky wooden gin palace, and on a Saturday night they would have New Orleans jazz bands playing there, people like Ken Colyer, and the Temperance Seven, and we loved it. The routine was to start out at L’Auberge in the early evening, have a couple of coffees, and then wander over the bridge of Eel Pie. I’ll never forget the feeling as you got about halfway across the bridge, and you’d suddenly realized you were in the middle of a swelling crowd of people who all looked vaguely the same. There was a tremendous sense of belonging back then. In those pre-hippie, beatnik days, it did seem to be all about the music. Drugs were rare, and even the drinking was fairly moderate.

I used to play there with Dave Brock, who later went on to found Hawkwind, and I fell in with the crowd of musicians and beatniks who used to hang out there. Sometimes we’d all jump on the train and go up to London to the folk clubs and pubs around Soho, places like the Marquess of Granby, the Duke of York, and the Gyre and Gimble coffee bar in Charing Cross. The first time I ever got beaten up was outside the “G’s.” A bunch of squaddies lured me outside and gave me a good kicking for absolutely no other reason, as far as I could see, than to let off steam. It was a pretty nasty experience, but in a perverse way I felt like I had made my bones, another rite of passage completed. It did teach me, however, that I was not cut out for fighting. I made no attempt to protect myself, maybe because I intuitively knew that would make matters worse, and from then on I seemed to develop an alert instinct for potentially violent situations and from then on avoided them like the plague.

The folk scene had a real following in those days, and in the clubs and pubs I began to meet loads of like-minded people and musicians. Long John Baldry was a regular, and I know Rod Stewart used to sing at the Duke of York, although I never saw him there. Also, two guitarists who used to play regularly in these places had a big influence on me. One was a guy called Buck, who played the first Zemaitis twelve-string I ever saw, and the other was Wiz Jones, another famous troubadour of the time. They’d play Irish ballads and English folk tunes, mixing them with Leadbelly songs and other stuff, which gave me a unique view of the world of folk music. I’d sit as close to them as possible, which was often difficult as they were so popular, and watch their hands to see the way they played. Then I’d come back home and practice for hours and hours, trying to teach myself to play the music I’d heard. I’d listen carefully to the recording of whatever song I was working on, then copy it and copy it till I could match it. I remember trying to imitate the bell-like tone achieved by Muddy Waters on his song “Honey Bee.” It was the first time I ever got three strings together on my guitar. I had no technique, of course; I just spent hours mimicking it.

The main man for me was Big Bill Broonzy, and I tried to learn his technique, which was to accompany yourself with your thumb, using the thumb to play eighth notes on the bass strings while you pick out a riff or countermelody with your fingers. This is a staple part of blues playing in one form or another and can be developed into a folk pattern, too, like clawhammer, where you move your thumb rhythmically between the bottom strings alternately while picking out the melody on the top strings with your first, second, and sometimes third fingers. My method of learning was pretty basic; I’d play along with the record I wanted to imitate, and when I thought I’d mastered something, I’d record it on the Grundig and play it back. If it sounded like the record, then I was satisfied. As I slowly began to master the art of finger-style acoustic playing, I learned new songs, for instance, the old Bessie Smith song “Nobody Knows When You’re Down and Out,” “Railroad Bill,” an old bluegrass song, and Big Bill Broonzy’s “Key to the Highway.”

Around that time I met, and followed around for a while, an American female folk singer named Gina Glaser. She was the first American musician I had been anywhere near, and I was starstruck. To make a little extra money, she posed naked for still life classes at Kingston Art School. She had a young child, and a slightly world-weary aura to her. Her specialty was old Civil War songs like “Pretty Peggyo” and “Marble Town.” She had a beautiful, clear voice and played an immaculate clawhammer style. I was smitten with her, and I think she found me attractive, but she was twice my age, and I was still pretty green around women.

As my playing improved, I started to go to a pub in Kingston called the Crown, where I used to play in a corner by the billiard table. This particular pub attracted a suave crowd of beat people, who seemed a cut above the kind of music fans I’d been hanging out with. This was an affluent crowd. The guys wore Chelsea boots, leather jackets, matelot shirts, and Levi 501s, which were incredibly hard to find—and a kind of harem of very-good-looking girls moved around with them. Bardot was then the icon for women to follow, so their uniform was tight jumpers, slit skirts, and black stockings with duffel coats and scarves.

They were very exotic, very fast, and very well educated, a tight group of friends who seemed to have grown up together. They’d usually meet at the pub, then go off to hang out at someone’s house, and there always seemed to be a party going on around them. It became my ambition to be accepted by this group, but since I was an outsider from the word go, and working-class, the only way I could really get their attention was by playing the guitar.

Hanging out with this bunch, and especially seeing all these beautiful girls, really made me want to belong, but I had no idea how to go about it. When I was still at secondary modern, a friend of mine, Steve, one of the lads from Send who was into clothes and looking cool, took me out on a blind date. I was obviously elected to divert his girlfriend’s mate, who wasn’t the most beautiful girl in the world. I wasn’t interested in her at all, but I was very horny, and although I wouldn’t kiss her, I did try to get my hands on her upper torso. She wasn’t amused and created a bit of a scene. That was as far as I got with sex until Diane at Hollyfield, and we hadn’t got much further. I was terrified of going too far and then being held responsible in some way. Ever since finding that pornography on the Green, I felt compelled to discover for myself what it was all about, but my experience of female rejection, stemming from my mother, left me quaking with fear at the threshold.

At Kingston, I set my sights on a girl who was completely out of my league. I think she was the daughter of a local politician from Chessington. Her name was Gail, and she was absolutely gorgeous, dark-skinned, tall, and voluptuous, with long, dark, curly hair.

She seemed very aloof when I first saw her, but after I had observed her for a few weeks, I could see that she was also pretty wild. I quickly became obsessed with her, and somehow got it into my head that the best way to get her attention was by regularly getting blind drunk, as if that would make me more appealing or more manly in some way. On any given night in Kingston, I would be drinking up to ten pints of Mackeson’s milk stout, followed by rum and black currant, gin and tonic, or gin and orange. I learned to try and drink so that I’d stop just short of passing out, but I would invariably end up getting very ill and throwing up. Needless to say, as a courting tool it failed miserably. Gail was not impressed, but if nothing else, I was learning a lot about the power of alcohol.

Only a short time before this, I had gone with three friends on the train to Beaulieu for the jazz festival. We got there on a Saturday morning and were planning to stay till Sunday night. We decided to go to the pub for lunch before going on to the festival. The last thing I remembered that day was dancing on the tables with a guy I’d never met before in my life, who became my absolute brother. I can still recall the way he looked and everything about him, though I’d never seen him before or since. I thought he was just the most funny, charismatic person I’d ever met in my life, and we got legless together.

I had gone with some friends, with the intention of camping in the woods near the festival, and the next thing I knew I was waking up in the morning on my own, in the middle of nowhere. I had no money, I had shit myself, I had pissed myself, I had puked all over myself, and I had no idea where I was. There were signs, like the remains of a fire, that the others had pitched camp close by, but they’d all gone and left me there. I was stunned. I had to get home to Ripley in this condition, and I caught the train at a little country station nearby. The stationmaster took pity on me and gave me a handwritten I.O.U. on a piece of paper, which I dejectedly gave to Rose when I got home. I was heavily disillusioned with my friends, shocked that they could have just left me there in that state, alone and without any money, but the really insane thing was, I couldn’t wait to do it all again.

I thought there was something otherworldly about the whole culture of drinking, that being drunk made me a member of some strange, mysterious club. It also gave me courage to play and, finally, to get off with a girl. Saturday nights in Kingston always followed the same routine. We would all meet up at the Crown and I would play. One guy who was always there, Dutch Mills, was a smooth character who played blues harmonica, and most Saturdays he would have a party at his house. I remember going back there one night with about a dozen people, none of whom I knew very well, and at some point the lights went off and everyone went at it. That’s where and when I actually lost my virginity, with a girl named Lucy who was older than me, and whose boyfriend was out of town. I was terrified and fumbly, I still am for that matter, but she patiently helped me through, and although I know all the others were aware of what was happening, either they didn’t care or were so busy with their own endeavors that they just chose to ignore us. The following morning we parted company, and although we saw one another around often, it was never spoken of again. With what I knew about relationships and sex, I just assumed that was the way it was done, and went on my way.

Going so suddenly from the odd kind of groping session to full intercourse was very, very strange, and it was all over in the blinking of an eye. I didn’t use any protection, of course, as the whole thing was so unexpected, so the next time I thought it was going to happen, I went with a mate of mine to a drugstore to buy a packet of Durex. It was incredibly embarrassing. I had been told to ask for a packet of three, which I assumed was some kind of code. I remember the man behind the counter smiling at me and giving me a kind of wink, and then asking me questions like “Do you want lubricated or nonlubricated?” I didn’t have a clue what he was talking about.

The next time I had the opportunity to use one of these things, it was at Dutch’s house. He had organized two girls, and we went back to his place in the afternoon. He went in one room and I went in the other, and I got this thing out of its wrapper, with absolutely no idea how to use it. I couldn’t quite get it on properly, and it was very slippery and weird, and I felt very embarrassed about it. Upon inspection, after the event, I realized that it had split, and I was filled with a sense of dread. Sure enough, a few weeks later the girl called me to tell me she thought she was pregnant, and that I had to get some money together for her to have an abortion. It gave me a shock even though such events were very commonplace at the time.

Sex was my only distraction from music, where I was beginning to seriously explore the blues. It’s very difficult to explain the effect the first blues record I heard had on me, except to say that I recognized it immediately. It was as if I were being reintroduced to something that I already knew, maybe from another, earlier life. For me there is something primitively soothing about this music, and it went straight to my nervous system, making me feel ten feet tall. This was the feeling I had when I first heard the Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee song on Uncle Mac, and the same thing happened when I first heard Big Bill Broonzy.

I saw a clip of him on TV, playing in a nightclub, lit by the light from a single lightbulb, swinging in its shade from the ceiling, creating an eerie lighting effect. The tune he was playing was called “Hey Hey,” and it knocked me out. It’s a complicated guitar piece, full of blue notes, which are what you get by splitting a major and a minor note. You usually start with the minor and then bend the note up toward the major, so it’s somewhere between the two. Indian and Gypsy music also use this kind of note bending. When I first heard Big Bill and, later, Robert Johnson, I became convinced that all rock ’n’ roll—and pop music too, for that matter—had sprung from this root.

Next I set about learning to play like Jimmy Reed, who usually plays a twelve-bar form, and whose style has been copied by countless R&B bands. I discovered that the key was to make a kind of boogie on the bottom two strings of the guitar by simply pressing down on the fifth string at the second fret and then the fourth fret to make a basic kind of walking figure, while playing the E string at the same time. Then I’d move it up to the next string to make the next part of the twelve-bar, and so on. The final step, and the hardest part really, is to feel it, to play in a relaxed rhythm so that it feels and sounds good. I am someone who can’t leave things unfinished, and if I’ve given myself a task to do in the day, then I can’t go to bed until I’ve done it. It was like this with the twelve-bar blues riff. I worked at it until it felt like it was part of my metabolism.

As I worked to improve my playing, I was meeting more and more people who had the same respect and reverence for the music I loved. One particular blues fanatic was Clive Blewchamp—we met at Hollyfield and set out together on a fantastic voyage of discovery. It was Clive who first played me the Robert Johnson album. He really enjoyed finding the hard-core stuff, the more obscure the better. We were also neck and neck in our dress sense and spent a lot of time together in and out of school. We would go to blues clubs, too, later on, and it was only when I started working full-time in bands that we stopped hanging out together. I always felt that he was a little contemptuous of what I was trying to do musically, as if it weren’t the real thing. Of course he was right, but I was unstoppable by then. He finished his term at Kingston after I was thrown out, got his diploma, and finally moved to Canada, where he ran a small R&B magazine. We stayed in touch over the years, until, sadly, he died, about ten years ago.

It was exciting to find that there existed this fellowship of like-minded souls, and this is one of the things that determined my future path toward becoming a musician. I started to meet people who knew about Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, and they had older friends, record collectors who would hold club nights, which is where I was first introduced to John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, and Little Walter. These guys would get together in one of their houses and spend the whole evening listening to one album, like The Best of Muddy Waters, and then have excited discussions about what they’d heard. Clive and me would often go up to London to visit record stores, like Imhoff’s on New Oxford Street, the whole of whose basement was devoted to jazz, and Dobell’s on Shaftesbury Avenue, where they had a bin devoted to Folkways, which was the major label for folk, blues, and traditional music. If you were lucky, you’d meet a working musician in one of these stores, and if you told them that you liked Muddy Waters, they might say, “Well, then you’ve got to listen to Lightning Hopkins,” and you’d be off in a new direction.

Music began to take up so much of my life that it was no surprise that my work at art school began to suffer. It was my own fault that things went this way, because initially I had been really gripped by the experience of getting involved in a life in art. I was quite hooked by painting, and to a certain extent by design. I was a good draftsman, and when I enrolled at Kingston, they had offered me a place in their graphics department, which I accepted rather than going into fine art. But once I’d got into the graphics department, I knew that I was in the wrong place, and I dropped out. My motivation died. I’d go into the canteen at lunch and see all the students come in from fine art, long-haired, covered in paint, and looking completely detached. They were given almost total freedom, developing their talents as painters or sculptors, while I was set to do projects every day, designing a soap box, or coming up with an advertising campaign for a new product.

Apart from a short period when I managed to get into the glass department, where I learned engraving and sandblasting, and became quite interested in contemporary stained glass, I was bored to tears. Music was ten times more exciting, ten times more engaging, and as much as I loved art, I also felt that the people who were trying to teach me were coming from an academic direction that I just couldn’t identify with. It seemed to me that I was being prepared for a career in advertising, not art, where salesmanship would be just as important as creativity. Consequently, my interest, and my output, dwindled down to nothing.

I was still shocked, however, when I went for my assessment at the end of the first year and was told that they had decided not to keep me on. I knew my portfolio was a bit thin, but I really believed that the work I had done was good enough to get me through. To me it was much more creative and imaginative than most of the other students’ work. But they were judging by quantity, and they booted me and one other student out, just two of us out of fifty, which was not good. I was totally unprepared for it, but it threw me back into using the only other talent I had.

Being thrown out of art school was another rite of passage for me. I got brought up short by the sudden realization that all doors weren’t going to open up for me for the rest of my life, that the truth was that some of them were going to close. Emotionally and mentally, the shit hit the fan. When I finally found the courage to tell Rose and Jack, they were bitterly disappointed and ashamed, because they found out that I was a liar as well as a failure. Many times when I had told them I was at school, I was actually playing hooky, just wandering around playing the guitar or hanging out in a pub drinking. “You’ve had your chance, Rick,” Jack said to me, “and now you’ve chucked it away.” He made it quite clear that if I intended to stay living with them, I would be expected to work and bring money into the house. If I didn’t contribute, then I could get out.

I chose to work, and accepted a job working for Jack as his “mate” at fifteen pounds a week, which was a good wage. Jack was a master plasterer, a master bricklayer, and a master carpenter. In layman’s terms, this means he had “mastered” all of these trades and was entitled to the wages and respect this commanded. Working for someone as elevated as this was no laughing matter, of course. It meant mixing up lots of plaster, mortar, and cement and getting it to him quickly, so that he could lay bricks and put up plaster without taking his eyes off the job. One of the first big jobs we did together was at a primary school in Chobham, and the most demanding work for me was carrying semiliquid mortar in a hod up a ladder and onto a scaffold as quickly as my body would allow so that Jack could lay a true line of bricks.

I got extremely fit, and I really did love the work, probably because I knew it would not last forever. My grandfather really was brilliant with his hands, and watching him plaster an entire wall in minutes was exhilarating. It turned out to be a valuable experience, even though it seemed he was being extra-tough on me, which I’m sure was because he wanted no suspicion of nepotism. I learned that he worked, and lived, from a very strong set of principles, which he tried to pass on to me. In those days, there were two schools of thought on a building site. The first was that you did as little as you could, but got away with it by making the foreman think you were really busy when you were in fact skiving. This seemed to be the norm. The second, as personified by Jack, was that you worked consistently to a rhythm and did a good job until you had finished it. He had no time for skivers, and so, to a certain extent, like me in later years, he was slightly unpopular and a bit of an outcast. His legacy to me was that I should always try to do my best, and always finish what I started.

All the time, I was working on my playing, sometimes almost driving my family mad with the repetitiveness of my practicing. I was addicted to music, and by now I also had a record collection. Listening to Chuck Berry, B. B. King, and Muddy Waters had turned me on in a big way to electric blues, and somehow I had managed to persuade my grandparents to buy me an electric guitar. This happened after I had been up to London to see Alexis Korner playing at the Marquee on Oxford Street, a jazz club that had occasional blues nights. Alexis had the first real R&B band in the country, with a fantastic harmonica player named Cyril Davies. Watching Alexis play for the first time made me think that there was no reason why an electric guitar shouldn’t be available to me.

Another good reason why I so desperately needed a new guitar was that my Washburn was broken beyond repair. Before I started working for Jack, Rose had decided to take me to visit my mum for a few days. She was then living on an air force base near Bremen, Germany, where her husband, Frank, or “Mac” as I called him, was stationed. She now had three children; a second daughter, Heather, was born in 1958. Almost as soon as I arrived, Mac told me that I would have to get my hair cut before I could go into the mess. I was horrified by this request, since my hair was not even particularly long by the standards of the day, but it seemed that the offensive part was that you couldn’t see the top of my ears. I looked to the younger generation, in the form of my three half siblings, for support, but found none there. One by one they came after me, too. I was adamant about not doing it, until Rose also joined their ranks, which broke my heart, because up until then she had always been my staunchest defender, whatever the situation. I gave in, but it made me very angry, as it seemed like I no longer had anyone on my side. They gave me a crew cut and I felt alone and humiliated.

I moped around a lot for the remainder of my stay, but things only got worse. One day I was sulking on my bed in the spare room when my half brother Brian came in and sat down on the bed without looking. He sat down right on top of my beloved Washburn guitar, which was lying there, and broke the neck clean in half. I could see immediately that it was beyond repair, and I was gutted. He was the sweetest kid, totally in awe of me, and it was an accident, but there and then I vowed internally that Pat and her entire family could go to hell. I didn’t lose my temper. I just withdrew. Not only had my identity been ripped away, but my most treasured possession had been destroyed. I went inside of myself and decided that from then on, I would trust nobody.

The electric guitar I chose was one I had had my eye on in the window of Bell’s, where we had got the Hoyer. It was the same guitar I had seen Alexis Korner playing, a double-cutaway semi-acoustic Kay, which at the time was quite an advanced instrument, although essentially, as I later learned, it was still only a copy of the best guitar of the day, the Gibson ES-335. It was cut away on both sides of the neck to allow easy access up the neck to the higher frets. You could play it acoustically, or plug it in and play electric. The Gibson would have cost over a hundred pounds then I think, well beyond our reach, while the Kay cost only ten pounds, but still seemed quite exotic. It captured my heart. The only thing that wasn’t quite right with it was the color. Though advertised as Sunburst, which would have been a golden orange going to dark red at the edges, it was more yellowy, going to a sort of pink, so as soon as I got it home, I covered it with black Fablon.

Much as I loved this guitar, I soon found out that it wasn’t that good. It was just as hard to play as the Hoyer, because again, the strings were too high off the fingerboard, and, because there was no truss rod, the neck was weak. So after a few months’ hard playing, it began to bow, something I had to adapt to, not having a second instrument. Something more profound also happened when I got this guitar. As soon as I got it, I suddenly didn’t want it anymore. This phenomenon was to rear its head throughout my life and cause many difficulties.

We hadn’t bought an amplifier, so I could only play it acoustically and fantasize about what it would sound like, but it didn’t matter. I was teaching myself new stuff all the time. Most of the time I was trying to play like Chuck Berry or Jimmy Reed, electric stuff, then I sort of worked backward into country blues. This was instigated by Clive, when out of the blue he gave me an album to listen to called King of the Delta Blues Singers, a collection of seventeen songs recorded by bluesman Robert Johnson in the 1930s. I read in the sleeve notes that when Johnson was auditioning for the sessions in a hotel room in San Antonio, he played facing into the corner of the room because he was so shy. Having been paralyzed with shyness as a kid, I immediately identified with this.

At first the music almost repelled me, it was so intense, and this man made no attempt to sugarcoat what he was trying to say, or play. It was hard-core, more than anything I had ever heard. After a few listenings I realized that, on some level, I had found the master, and that following this man’s example would be my life’s work. I was totally spellbound by the beauty and eloquence of songs like “Kindhearted Woman,” while the raw pain expressed in “Hellhound on My Trail” seemed to echo things I had always felt.