[/caption]

[/caption]DESCRIPTION

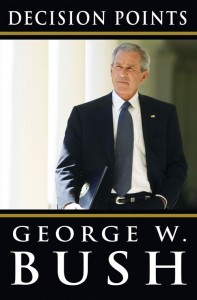

In this candid and gripping account, President George W. Bush describes the critical decisions that shaped his presidency and personal life.George W. Bush served as president of the United States during eight of the most consequential years in American history. The decisions that reached his desk impacted people around the world and defined the times in which we live._

Decision Points_ brings readers inside the Texas governor's mansion on the night of the 2000 election, aboard Air Force One during the harrowing hours after the attacks of September 11, 2001, into the Situation Room moments before the start of the war in Iraq, and behind the scenes at the White House for many other historic presidential decisions.

For the first time, we learn President Bush's perspective and insights on:

His decision to quit drinking and the journey that led him to his Christian faith

The selection of the vice president, secretary of defense, secretary of state, Supreme Court justices, and other key officials

His relationships with his wife, daughters, and parents, including heartfelt letters between the president and his father on the eve of the Iraq War

His administration's counterterrorism programs, including the CIA's enhanced interrogations and the Terrorist Surveillance Program

Why the worst moment of the presidency was hearing accusations that race played a role in the federal government’s response to Hurricane Katrina, and a critical assessment of what he would have done differently during the crisis

His deep concern that Iraq could turn into a defeat costlier than Vietnam, and how he decided to defy public opinion by ordering the troop surge

His legislative achievements, including tax cuts and reforming education and Medicare, as well as his setbacks, including Social Security and immigration reform

The relationships he forged with other world leaders, including an honest assessment of those he did and didn’t trust

Why the failure to bring Osama bin Laden to justice ranks as his biggest disappointment and why his success in denying the terrorists their fondest wish—attacking America again—is among his proudest achievements

A groundbreaking new brand of presidential memoir, Decision Points will captivate supporters, surprise critics, and change perspectives on eight remarkable years in American history—and on the man at the center of events.

Since leaving office, President George W. Bush has led the George W. Bush Presidential Center at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas. The center includes an active policy institute working to advance initiatives in the fields of education reform, global health, economic growth, and human freedom, with a special emphasis on promoting social entrepreneurship and creating opportunities for women around the world. It will also house an official government archive and a state-of-the-art museum that will open in 2013.

About the Author

George W. Bush is the 43rd President of the United States.

REVIEWS

"That is the nature of the presidency. Perceptions are shaped by the clarity of hindsight. In the moment of decision, you don't have that advantage." -G. BushIn a lot of ways this statement just about sums up the book. The President of the United States, maybe more so than any other person on the face of the Earth, has his/her every decision microscopically analyzed by just about everyone... after the fact, when the results are known and more information is available. I thought this to be a very interesting premise for a presidential memoir. It doesn't come across as an apology nor does it come across as an excuse. President Bush gives you the situation as he saw it and lets you make your own decision.

I am not a huge fan of President Bush, but I don't think he is the utter failure as President that some consider him. I come away with some empathy (though short of being President, I don't think anyone could truly grasp the reality) for President Bush. Could things have been done better... more than likely. Could they have been worse... almost certainly... but how many of us couldn't apply those phrases to our own lives?

If you are a Bush fan, I'd almost guarantee you'll like the book. If you aren't a fan.... you'll probably find some more ammunition to bash him. For myself, I don't at all regret the time spent reading the book and that is usually the measure that I put on literary material.

PREVIEW

[lyrics]In the final year of my presidency, I began to think seriously about writing my memoirs. On the recommendation of Karl Rove, I met with more than a dozen distinguished historians. To a person, they told me I had an obligation to write. They felt it was important that I record my perspective on the presidency, in my own words.

“Have you ever seen the movie Apollo 13?” the historian Jay Winik asked. “Everyone knows the astronauts make it home in the end. But you’re on the edge of your seat wondering how they do it.”

Nearly all the historians suggested that I read Memoirs by President Ulysses S. Grant, which I did. The book captures his distinctive voice. He uses anecdotes to re-create his experience during the Civil War. I could see why his work had endured.

Like Grant, I decided not to write an exhaustive account of my life or presidency. Instead I have told the story of my time in the White House by focusing on the most important part of the job: making decisions. Each chapter is based on a major decision or a series of related decisions. As a result, the book flows thematically, not in a day-by-day chronology. I do not cover all of the important issues that crossed my desk. Many devoted members of my Cabinet and staff are mentioned briefly or not at all. I value their service, and I will always be grateful for their contributions.

My goals in writing this book are twofold. First, I hope to paint a picture of what it was like to serve as president for eight consequential years. I believe it will be impossible to reach definitive conclusions about my presidency—or any recent presidency, for that matter—for several decades. The passage of time allows passions to cool, results to clarify, and scholars to compare different approaches. My hope is that this book will serve as a resource for anyone studying this period in American history.

Second, I write to give readers a perspective on decision making in a complex environment. Many of the decisions that reach the president’s desk are tough calls, with strong arguments on both sides. Throughout the book, I describe the options I weighed and the principles I followed. I hope this will give you a better sense of why I made the decisions I did. Perhaps it will even prove useful as you make choices in your own life.

Decision Points is based primarily on my recollections. With help from researchers, I have confirmed my account with government documents, contemporaneous notes, personal interviews, news reports, and other sources, some of which remain classified. There were instances in which I had to rely on my memory alone. If there are inaccuracies in this book, the responsibility is mine.

In the pages that follow, I have done my best to write about the decisions I got right, those I got wrong, and what I would do differently if given the chance. Of course, in the presidency, there are no do-overs. You have to do what you believe is right and accept the consequences. I tried to do that every day of my eight years in office. Serving as president was the honor of a lifetime, and I appreciate your giving me an opportunity to share my story.

It was a simple question. “Can you remember the last day you didn’t have a drink?” Laura asked in her calm, soothing voice. She wasn’t threatening or nagging. She did expect an answer. My wife is the kind of person who picks her moments. This was one of them.

“Of course I can,” came my indignant response. Then I thought back over the previous week. I’d had a few beers with the guys on Monday night. On Tuesday I’d fixed myself my favorite after-dinner drink: B&B, Benedictine and brandy. I’d had a couple of bourbon and Sevens after I put Barbara and Jenna to bed on Wednesday. Thursday and Friday were beer-drinking nights. On Saturday, Laura and I had gone out with friends. I’d had martinis before dinner, beers with dinner, and B&Bs after dinner. Uh-oh, I had failed week one.

I went on racking my memory for a single dry day over the past few weeks; then the past month; then longer. I could not remember one. Drinking had become a habit.

I have a habitual personality. I smoked cigarettes for about nine years, starting in college. I quit smoking by dipping snuff. I quit that by chewing long-leaf tobacco. Eventually I got down to cigars.

For a while I tried to rationalize my drinking habit. I was nowhere near as bad as some of the drunks I knew in our hometown of Midland, Texas. I didn’t drink during the day or at work. I was in good shape and jogged almost every afternoon, another habit.

Over time I realized I was running not only to stay fit, but also to purge my system of the poisons. Laura’s little question provoked some big ones of my own. Did I want to spend time at home with our girls or stay out drinking? Would I rather read in bed with Laura or drink bourbon by myself after the family had gone to sleep? Could I continue to grow closer to the Almighty, or was alcohol becoming my god? I knew the answers, but it was hard to summon the will to make a change.

In 1986, Laura and I both turned forty. So did our close friends Don and Susie Evans. We decided to hold a joint celebration at The Broadmoor resort in Colorado Springs. We invited our childhood friends Joe and Jan O’Neill, my brother Neil, and another Midland friend, Penny Sawyer.

The official birthday dinner was Saturday night. We had a big meal, accompanied by numerous sixty-dollar bottles of Silver Oak wine. There were lots of toasts—to our health, to our kids, to the babysitters who were watching the kids back home. We got louder and louder, telling the same stories over and over. At one point Don and I decided we were so cute we should take our routine from table to table. We shut the place down, paid a colossal bar tab, and went to bed.

I awoke the next morning with a mean hangover. As I left for my daily jog, I couldn’t remember much of the night before. About halfway through the run, my head started to clear. The crosscurrents in my life came into focus. For months I had been praying that God would show me how to better reflect His will. My Scripture readings had clarified the nature of temptation and the reality that the love of earthly pleasures could replace the love of God. My problem was not only drinking; it was selfishness. The booze was leading me to put myself ahead of others, especially my family. I loved Laura and the girls too much to let that happen. Faith showed me a way out. I knew I could count on the grace of God to help me change. It would not be easy, but by the end of the run, I had made up my mind: I was done drinking.

When I got back to the hotel room, I told Laura I would never have another drink. She looked at me like I was still running on alcohol fumes. Then she said, “That’s good, George.”

I knew what she was thinking. I had talked about quitting before, and nothing had come of it. What she didn’t know was that this time I had changed on the inside—and that would enable me to change my behavior forever.

It took about five days for the freshness of the decision to wear off. As my memory of the hangover faded, the temptation to drink became intense. My body craved alcohol. I prayed for the strength to fight off my desires. I ran harder and longer as a way to discipline myself. I also ate a lot of chocolate. My body was screaming for sugar. Chocolate was an easy way to feed it. This also gave me another motivation for running: to keep the pounds off.

Laura was very supportive. She sensed that I really was going to quit. Whenever I brought up the subject, she urged me to stay with it. Sometimes I talked about drinking again just to hear her encouraging words.

My friends helped, too, even though most of them did not stop drinking when I was around. At first it was hard to watch other people enjoy a cocktail or a beer. But being the sober guy helped me realize how mindless I must have sounded when I drank. The more time passed, the more I felt momentum on my side. Not drinking became a habit of its own—one I was glad to keep.

Quitting drinking was one of the toughest decisions I have ever made. Without it, none of the others that follow in this book would have been possible. Yet without the experiences of my first forty years, quitting drinking would not have been possible either. So much of my character, so many of my convictions, took shape during those first four decades. My journey included challenges, struggles, and failures. It is testimony to the strength of love, the power of faith, and the truth that people can change. On top of that, it was one interesting ride.

I am the first son of George and Barbara Bush. My father wore the uniform in World War II, married his sweetheart as soon as he came home, and quickly started a new family. The story was common to many young couples of their generation. Yet there was always something extraordinary about George H.W. Bush.

When Pearl Harbor was attacked, Dad was a high school senior. He had been accepted to Yale. Instead he enlisted in the Navy on his eighteenth birthday and became the youngest pilot to earn his wings. Before he shipped off for the Pacific, he fell in love with a beautiful girl named Barbara Pierce. He immediately told friends he would marry her. As a reminder, he painted her name on the side of his plane.

The Navy officer and his beautiful young bride.

One morning in September 1944, Dad was flying a mission over Chichi-Jima, an island occupied by the Japanese. His TBM Avenger was struck by enemy fire, but he kept going—diving at two hundred miles per hour—until he had dropped his bombs and hit the target. He shouted for his flight mates to bail out and then did so himself. Alone in the South Pacific, he swam to the tiny rubber raft that had been his seat cushion. When Dad was rescued by a submarine, he was told he could go home. He rejoined his squadron instead. His tour ended just before Christmas, and on January 6, 1945, he married Mother at her family church in Rye, New York.

After the war, Mother and Dad moved to New Haven so he could attend Yale. He was a fine athlete—a first baseman and captain of the baseball team. Mother came to almost every game, even during the spring of 1946, when she was pregnant with me. Fortunately for her, the stadium included a double-wide seat behind home plate designed for former law professor William Howard Taft.

Dad excelled in the classroom, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in just two and a half years. I attended his commencement in Mother’s arms, dozing through much of the ceremony. It wouldn’t be the last time I slept through a Yale lecture.

On Dad’s shoulders at Yale, age nine months.

Years later, millions of Americans would learn Dad’s story. But from the beginning, I knew it by heart. One of my first memories is of sitting on the floor with Mother looking through scrapbooks. She showed me photos from Dad’s pilot training in Corpus Christi, box scores from his games in the College World Series, and a famous picture of him with Babe Ruth on the pitcher’s mound at Yale Field. I pored over photos from their wedding: the Navy officer and his smiling young bride. My favorite part of the scrapbook was a piece of rubber from the raft that saved Dad’s life in the Pacific. I would bug him to tell stories from the war. He refused to brag. But Mother would. She adored him, and so did I. As I got older, there would be others I looked up to. But the truth is that I never had to search for a role model. I was the son of George Bush.

When Dad graduated in 1948, most assumed he would head to Wall Street. After all, his father was a partner at a successful investment house. But Dad wanted to make it on his own. So he and Mother loaded up their red Studebaker and moved west. I’ve always admired them for taking a risk, and I’ve always been grateful they settled where they did. One of my greatest inheritances is that I was raised in West Texas.

We spent our first year in the blue-collar town of Odessa, where there were few paved streets and frequent dust storms. We lived in a tiny apartment and shared a bathroom with—depending on whom you ask—either one or two prostitutes. Dad’s job was on the bottom rung of an oil services company. His duties included sweeping warehouses and painting pump jacks. A fellow worker once asked Dad if he was a college man. Dad told him yes, as a matter of fact, he had gone to Yale. The guy paused a second and replied, “Never heard of it.”

After a brief stint in California, we moved back to West Texas in 1950. We settled in Midland, the place I picture when I think of growing up. Midland was twenty miles east of Odessa. Native trees did not exist. The ground was flat, dry, and dusty. Beneath it sat a sea of oil.

Midland was the capital of the Permian Basin, which accounted for about 20 percent of America’s oil production in the 1950s. The town had an independent, entrepreneurial feel. There was fierce competition, especially in the oil business. But there was also a sense of community. Anybody could make it, anyone could fail. My friends’ parents did all sorts of jobs. One painted houses. One was a surgeon. Another poured cement. About ten blocks away lived a home builder, Mr. Harold Welch. A quarter century passed before I met him and courted his sweet daughter, Laura Lane.

Life in Midland was simple. I rode bikes with pals like Mike Proctor, Joe O’Neill, and Robert McCleskey. We went on Cub Scout trips, and I sold Life Savers door-to-door for charity. My friends and I would play baseball for hours, hitting each other grounders and fly balls until Mother called over the fence in our yard for me to come in for dinner. I was thrilled when Dad came out to play. He was famous for catching pop-ups behind his back, a trick he learned in college. My friends and I tried to emulate him. We ended up with a lot of bruises on our shoulders.

A typical Midland day, playing baseball until sunset.

One of the proudest moments of my young life came when I was eleven years old. Dad and I were playing catch in the yard. He fired me a fastball, which I snagged with my mitt. “Son, you’ve arrived,” he said with a smile. “I can throw it to you as hard as I want.”

Those were comfortable, carefree years. The word I’d use now is idyllic. On Friday nights, we cheered on the Bulldogs of Midland High. On Sunday mornings, we went to church. Nobody locked their doors. Years later, when I would speak about the American Dream, it was Midland I had in mind.

Amid this happy life came a sharp pang of sorrow. In the spring of 1953 my three-year-old sister Robin was diagnosed with leukemia, a form of cancer that was then virtually untreatable. My parents checked her into Memorial Sloan-Kettering in New York City. They hoped for a miracle. They also knew that researchers would learn from studying her disease.

With my sister, Robin, on her last Christmas, 1952.

Mother spent months at Robin’s bedside. Dad shuttled back and forth between Texas and the East Coast. I stayed with my parents’ friends. When Dad was home, he started getting up early to go to work. I later learned he was going to church at 6:30 every morning to pray for Robin.

My parents didn’t know how to tell me my sister was dying. They just said she was sick back east. One day my teacher at Sam Houston Elementary School in Midland asked me and a classmate to carry a record player to another wing of the school. While we were hauling the bulky machine, I was shocked to see Mother and Dad pull up in our family’s pea-green Oldsmobile. I could have sworn that I saw Robin’s blond curls in the window. I charged over to the car. Mother hugged me tight. I looked in the backseat. Robin was not there. Mother whispered, “She died.” On the short ride home, I saw my parents cry for the first time in my life.

Robin’s death made me sad, too, in a seven-year-old way. I was sad to lose my sister and future playmate. I was sad because I saw my parents hurting so much. It would be many years before I could understand the difference between my sorrow and the wrenching pain my parents felt from losing their daughter.

The period after Robin’s death was the beginning of a new closeness between Mother and me. Dad was away a lot on business, and I spent almost all my time at her side, showering her with affection and trying to cheer her up with jokes. One day she heard Mike Proctor knock on the door and ask if I could come out and play. “No,” I told him. “I have to stay with Mother.”

For a while after Robin’s death I felt like an only child. Brother Jeb, seven years younger than me, was just a baby. My two youngest brothers, Neil and Marvin, and my sister Doro arrived later. As I got older, Mother continued to play a big role in my life. She was the Cub Scout den mother who drove us to Carlsbad Caverns, where we walked among the stalactites and stalagmites. As a Little League mom, she kept score at every game. She took me to the nearest orthodontist in Big Spring and tried to teach me French in the car. I can still picture us riding through the desert with me repeating, “Ferme la bouche … ouvre la fenêtre.” If only Jacques Chirac could have seen me then.

On a trip with Mother in the desert.

Along the way, I picked up a lot of Mother’s personality. We have the same sense of humor. We like to needle to show affection, and sometimes to make a point. We both have tempers that can flare rapidly. And we can be blunt, a trait that gets us in trouble from time to time. When I ran for governor of Texas, I told people that I had my daddy’s eyes and my mother’s mouth. I said it to get a laugh, but it was true.

Being the son of George and Barbara Bush came with high expectations, but not the kind many people later assumed. My parents never projected their dreams onto me. If they hoped I would be a great pitcher, or political figure, or artist (no chance), they never told me about it. Their view of parenting was to offer love and encourage me to chart my own path.

They did set boundaries for behavior, and there were times when I crossed them. Mother was the enforcer. She could get hot, and because we had such similar personalities, I knew how to light her fuse. I would smart off, and she would let me have it. If I was smutty, as she put it, I would get my mouth washed out with soap. That happened more than once. Most of the time I did not try to provoke her. I was a spirited boy finding my own way, just as she was finding hers as a parent. I’m only half joking when I say I’m responsible for her white hair.

As I got older, I came to see that my parents’ love was unconditional. I know because I tested it. I had two car wrecks when I was fourteen, the legal driving age back then. My parents still loved me. I borrowed Dad’s car, carelessly charged in reverse, and tore the door off. I poured vodka in the fishbowl and killed my little sister Doro’s goldfish. At times I was surly, demanding, and brash. Despite it all, my parents still loved me.

Eventually their patient love affected me. When you know you have unconditional love, there is no point in rebellion and no need to fear failure. I was free to follow my instincts, enjoy my life, and love my parents as much as they loved me.

One day, shortly after I learned to drive and while Dad was away on a business trip, Mother called me into her bedroom. There was urgency in her voice. She told me to drive her to the hospital immediately. I asked what was wrong. She said she would tell me in the car.

As I pulled out of the driveway, she told me to drive steadily and avoid bumps. Then she said she had just had a miscarriage. I was taken aback. This was a subject I never expected to be discussing with Mother. I also never expected to see the remains of the fetus, which she had saved in a jar to bring to the hospital. I remember thinking: There was a human life, a little brother or sister.

Mother checked herself into the hospital and was taken to an exam room. I paced up and down the hallway to steady my nerves. After I passed an older woman several times, she said, “Don’t worry, honey, your wife will be just fine.”

When I was allowed into Mother’s room, the doctor said she would be all right, but she needed to spend the night. I told Mother what the woman had said to me in the hall. She laughed one of her great, strong laughs, and I went home feeling much better.

The next day I went back to the hospital to pick her up. She thanked me for being so careful and responsible. She also asked me not to tell anyone about the miscarriage, which she felt was a private family matter. I respected her wish, until she gave me permission to tell the story in this book. What I did for Mother that day was small, but it was a big deal for me. It helped deepen the special bond between us.

While I was growing up in Texas, the rest of the Bush family was part of a very different world. When I was about six years old, we visited Dad’s parents in Greenwich, Connecticut. I was invited to eat dinner with the grown-ups. I had to wear a coat and tie, something I never did in Midland outside of Sunday school. The table was set elegantly. I had never seen so many spoons, forks, and knives, all neatly lined up. A woman dressed in black with a white apron served me a weird-looking red soup with a white blob in the middle. I took a little taste. It was terrible. Soon everyone was looking at me, waiting for me to finish this delicacy. Mother had warned me to eat everything without complaining. But she forgot to tell the chef she had raised me on peanut butter and jelly, not borscht.

I had heard a lot about my paternal grandparents from Dad. My grandfather Prescott Bush was a towering man—six foot four, with a big laugh and a big personality. He was well known in Greenwich as a successful businessman with unquestioned integrity and a longtime moderator of the town assembly. He was also an outstanding golfer who was president of the U.S. Golf Association and once shot sixty-six in the U.S. Senior Open.

In 1950, Gampy, as we all called him, ran for the Senate. He lost by just over a thousand votes and swore off politics. But two years later, Connecticut Republicans persuaded him to try again. This time he won.

My grandparents, Prescott and Dorothy Walker Bush, campaigning for the U.S. Senate in Connecticut.

When I was ten years old, I went to visit Gampy in Washington. He and my grandmother took me to a gathering at a Georgetown home. As I wandered among the adults, Gampy grabbed my arm. “Georgie,” he said, “I want you to meet someone.” He led me toward a giant man, the only person in the room as tall as he was.

“I’ve got one of your constituents here,” Gampy said to the man. A huge hand swallowed mine. “Pleased to meet you,” said Gampy’s colleague, Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson.

My grandfather could be a very stern man. He was from the “children should be seen but not heard” school, which was foreign to a chatty little wiseacre like me. He doled out discipline quickly and forcefully, as I found out when he chased me around the room after I had pulled the tail of his favorite dog. At the time, I thought he was scary. Years later, I learned that this imposing man had a tender heart: Mother told me how he had comforted her by choosing a beautiful grave site for Robin in a Greenwich cemetery. When my grandfather died in 1972, he was buried at her side.

Dad loved and respected his father; he adored his mom. Dorothy Walker Bush was like an angel. We called her Ganny, and she was possibly the sweetest person I have ever met. I remember her tucking me into bed when I was little, tickling my back as we said nightly prayers. She was humble, and taught us never to brag. She lived to see Dad become president and died at age ninety-one, a few weeks after his defeat in 1992. Dad was with her in the final moments. She asked him to read to her from the Bible next to her bed. As he opened it, a bundle of old papers slipped out. They were letters Dad had written her years ago. She had cherished them all her life, and wanted them near her at the end.

Mother’s parents lived in Rye, New York. Her mother, Pauline Robinson Pierce, died when I was three. She was killed in a car accident when my grandfather Marvin, who was driving, reached down to stop a cup of hot coffee from spilling. The car swerved off the road and hit a stone wall. My little sister was named in my grandmother’s memory.

I was very fond of Mother’s father, Marvin Pierce, known as Monk. He had lettered in four sports at Miami University of Ohio, which gave him a mythic aura in my young eyes. He was president of McCall’s and a distant relative of President Franklin Pierce. I remember him as a gentle, patient, and humble man.

My trips back east taught me two important lessons: First, I could make myself comfortable in just about any environment. Second, I really liked living in Texas. Of course, there was one big advantage to being on the East Coast: I could watch major league baseball. When I was about ten years old, my kind uncle Bucky, Dad’s youngest brother, took me to a New York Giants game in the Polo Grounds. I still remember the day I watched my hero, Willie Mays, play the outfield.

Five decades later I saw Willie again, when he served as honorary commissioner for a youth T-ball game on the South Lawn of the White House. He was seventy-five years old, but he still seemed like the Say Hey Kid to me. I told the young ballplayers that day, “I wanted to be the Willie Mays of my generation, but I couldn’t hit a curveball. So, instead, I ended up being president.”

In 1959 my family left Midland and moved 550 miles across the state to Houston. Dad was the CEO of a company in the growing field of offshore drilling, and it made sense for him to be close to his rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. Our new house was in a lush, wooded area that was often pelted by rainstorms. This was the exact opposite of Midland, where the only kind of storm you got was a dust storm. I was nervous about the move, but Houston was an exciting city. I learned to play golf, made new friends, and started at a private school called Kinkaid. At the time, the differences between Midland and Houston seemed big. But they were nothing compared to what was coming next.

One day after school, Mother was waiting at the end of our driveway. I was in the ninth grade, and mothers never came out to meet the bus—at least mine didn’t. She was clearly excited about something. As I got off the bus, she let it out: “Congratulations, George, you’ve been accepted to Andover!” This was good news to her. I wasn’t so sure.

Dad had taken me to see his alma mater, Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, the previous summer. It sure was different from what I was used to. Most of the dorms were large brick buildings arranged around quads. It looked like a college. I liked Kinkaid, but the decision had been made. Andover was a family tradition. I was going.

My first challenge was explaining Andover to my friends in Texas. In those days, most Texans who went away to high school had discipline problems. When I told a friend that I was headed to a boarding school in Massachusetts, he had only one question: “Bush, what did you do wrong?”

When I got to Andover in the fall of 1961, I thought he might be on to something. We wore ties to class, to meals, and to the mandatory church services. In the winter months, we might as well have been in Siberia. As a Texan, I identified four new seasons: icy snow, fresh snow, melting snow, and gray snow. There were no women, aside from those who worked in the library. Over time, they began to look like movie stars to us.

The school was a serious academic challenge. Going to Andover was the hardest thing I did until I ran for president almost forty years later. I was behind the other students academically and had to study like mad. In my first year, the lights in our dorm rooms went out at ten o’clock, and many nights I stayed up reading by the hall light that shined under the door.

I struggled most in English. For one of my first assignments, I wrote about the sadness of losing my sister Robin. I decided I should come up with a better word than tears. After all, I was on the East Coast and should try to be sophisticated. So I pulled out the Roget’s Thesaurus Mother had slipped into my luggage and wrote, “Lacerates were flowing down my cheeks.”

When the paper came back, it had a huge zero on the front. I was stunned and humiliated. I had always made good grades in Texas; this marked my first academic failure. I called my parents and told them I was miserable. They encouraged me to stay. I decided to tough it out. I wasn’t a quitter.

Home in Houston on a break from Andover. Because of the age difference, I felt more like an uncle than a brother to my siblings in those days.

My social adjustment came faster than my academic adjustment. There was a small knot of fellow Texans at Andover, including a fellow from Fort Worth named Clay Johnson. We spoke the same language and became close friends. Soon I broadened my circle. For a guy who was interested in people, Andover was good grazing.

I discovered that I was a natural organizer. My senior year at Andover, I appointed myself commissioner of our stickball league. I called myself Tweeds Bush, a play on the famous New York political boss. I named a cabinet of aides, including a head umpire and a league psychologist. We devised elaborate rules and a play-off system. There was no wild card; I’m a purist.

We also came up with a scheme to print league identification cards, which conveniently could double as fake IDs. The plan was uncovered by school authorities. I was instructed to cease and desist, which I did. In my final act as commissioner, I appointed my successor, my cousin Kevin Rafferty.

That final year at Andover, I had a history teacher named Tom Lyons. He liked to grab our attention by banging one of his crutches on the blackboard. Mr. Lyons had played football at Brown University before he was stricken by polio. He was a powerful example for me. His lectures brought historical figures to life, especially President Franklin Roosevelt. Mr. Lyons loved FDR’s politics, and I suspect he found inspiration in Roosevelt’s triumph over his illness.

Mr. Lyons pushed me hard. He challenged, yet nurtured. He hectored and he praised. He demanded a lot, and thanks to him I discovered a life-long love for history. Decades later, I invited Mr. Lyons to the Oval Office. It was a special moment for me: a student who was making history standing next to the man who had taught it to him so many years ago.

[/lyrics]

DETAILS

TITLE: Decision Points

Author: George W. Bush

Language: English

ISBN: 9780307590619

Format: TXT, EPUB, MOBI

DRM-free: Without Any Restriction

SHARE LINKS

Mediafire (recommended)Rapidshare

Megaupload

No comments:

Post a Comment